He was a driving force and often an organiser in that gallery throughout the 1960s. Exhibition venues were hard to find in Milan in those days, and many artists used it (including Agnetti, Grignani, Ballocco, Meseus, Gambone, Scheggi and Calderara), and La Pietra would always continue to work closely with them. The gallery often pursued research and collaborative ventures, such as the synesthetic projects of ’63/’64 with sculptors Marchese, Benevelli and Azuma, or with Nanda Vigo for the competition to design the Monument to the Resistance in Brescia.

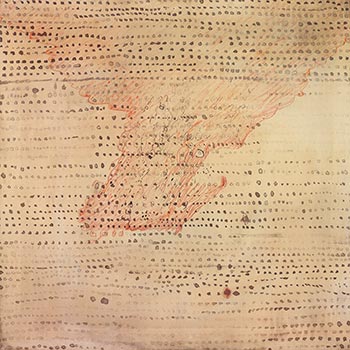

The first signs of a maturing approach were discerned in ’64/’65 by Gillo Dorfles, who, in introducing La Pietra’s works for an exhibition, was the first to term some of his chaos-infused signs random; they decomposed an acquired equilibrium into easily recognisable gestural signs within a predetermined schema. Dorfles would often give La Pietra the opportunity to participate in many exhibitions and festivals in what was then known as the “nuova tendenza” (new wave).

By the mid 1960s, this disruption in the predetermined schema would become a theme that recurred in a series of his architectural and furniture studies and works (the Altre Cose boutique in Milan being an exemplar). The awareness of these theories and their application, not only in two dimensions but also with objects and environmental installations, led him in 1967 to formulate what would become known, especially in radical-design and architectural circles, as the Theory of the Disequilibrating system. This theory would inspire La Pietra’s works, studies and writings until the end of the 1970s; it existed, in effect, to enable him to work unencumbered by a “system”.

To work, yes, but outside or at least on the margins of a system, that of a subjugated art or architecture profession. His refusal was prompted not only by a cultural and political position that was widespread among the art avant-garde of the time but also, as would become clear, by a desire to reclaim a sufficiently independent space for exploration and experimentation within the creative disciplines that operate in a production-for-profit scenario.

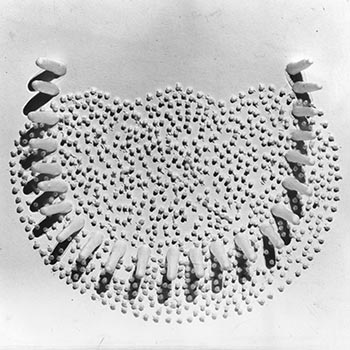

In the name of these experimental explorations, from as early as the 1960s, La Pietra experimented with a whole host of innovations: new materials (building an “art/craft” workshop to work with methacrylate); new types of furnishing, bringing together a boutique (Altre Cose) and a disco (Bang Bang) in Milan; new electronic technologies (using a dimmer for the first time in his Globo tissurato (textured globe) lamp or his luxofono applied to the audiovisual spaces presented at the Toselli gallery and in the audiovisual space at the Milan Triennale); new technologies for architecture (the inflatable pavilion for the Osaka Expo or the silicalcite prefabrication systems); new kinds of object (viz. the Uno sull’altro – One on top of another – bookshelf produced by Poggi); and new fields of research and experimentation in studying suburban areas (initially with Livio Marzot), exploring aesthetic interventions on an urban scale (see Campo Urbano in Como or Zafferana Etnea near Catania).

Towards the end of the 1960s, he contributed to cutting-edge artistic developments (conceptual art) and to the environmental experimentation that would later be termed radical design and architecture.