Informed by these considerations, his work would often come into contact with early-’80s research – in (postmodern) architecture or design (with Memphis and Alchimia), for example. But, precisely because of his continual references to memory, the spectacular and the conceptual, he would soon come out in favour of a neo-eclecticism that could embrace diversity with confidence. This trajectory would lead him into ever-deeper, more veiled areas, seldom-trodden paths, through his deep-rooted belief in “operating by breaking all taboos”.

The ultimate taboo that he tackled concerned the tradition of our material culture, taking a closer look at the world of period production. Until the mid ’80s, the classic “period” furniture piece was the province of a type of producer/artisan often termed “forgers”, who remade objects from the past. With his 1985 film Classico contemporaneo, he revisited this cultural area, bringing “handmade production”, the “remake” and “the traditional techniques to renew through design” to the attention of producers and the cultural world.

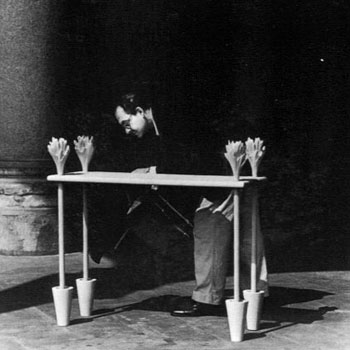

In the exhibitions Abitare il tempo (Inhabiting time) at Verona Fair and Abitare con arte (Living with art) in the former church of San Carpoforo in Milan, he demonstrated how the value of the material and of how it is transformed, with traditional techniques revisited for a contemporary design, can be rediscovered. The shows used his own works and those of hundreds of artists, architects and designers (collaborating, often for the first time, with classic- and traditional-furniture manufacturers).

Other projects found La Pietra scouring the late-’60s “urban fringe” for “marginal cultures”. With the Bathing culture, his series of exhibitions and seminars shone a fresh spotlight on the behaviours, forms and signs of this “autonomous culture”, whose system of signs yielded further ideas for his drawings, pictures and objects.

In this period, his pictures teemed with new forms, drawing ever more strongly on Mediterranean culture. His objects often referenced the works of Ponti, whom he studied avidly. In mid decade, he would write the first monograph on the great architect, filling the void left by historians who for various reasons had been unwilling or unable to approach the work of this key 20th-century figure. Ponti and Ulrich returned to prominence thanks to La Pietra, whose monographs showed his interest in those “applied arts” that Italian design had forgotten.

With the “Genius loci” exhibition (Abitare il tempo, 1987), La Pietra began a “crusade” to rediscover promising areas of material culture to refresh with an infusion of “design culture”. These were extremely active years. He taught at the Istituto Statale in Monza; he was an adjunct professor in the architecture faculties at Turin, Venice and Palermo; he edited Domus and then ran Area magazine and Abitare con arte; he organised exhibitions; he entered numerous architectural competitions; he showed new pictures in various galleries in Italy and overseas; he even played two nights a week with the Global Jazz Gang for several years (at Capolinea, Santa Tecla, Club Due and the Scimmie, Milan). But above all, he drew and drew and drew.

It was an action-packed, enthusiasm-fuelled decade. He often worked in institutions but never let himself get too involved. Consequently, he won no recognition. His only major award came, at decade’s end, from a long-time admirer: Eugenio Battisti, who presented him with the “Utopia Prize” at the International Congress on Utopias in Rome.