La Pietra’s status as a radical architect and artist in the early 1970s was fully acknowledged in the exhibitions at the Milan Triennale, in the exhibition “Italy: the new domestic landscape” at the MoMA in New York, in the “Trigon 71” show at the Neue Galerie in Graz, in the exhibition curated by Gillo Dorfles on Italian art at Museum am Ostwal, Dortmund, and at the 1972 Venice Biennale. Yet the recognition would not stunt his tireless experimentation. Indeed, he was a leading exponent in the group of artists who worked with cinema (with Barucchello, Patella, Carpi and Nespolo, coordinated by Vittorio Fagone) and who contributed to all the exhibitions in Italy and abroad on experimental or art cinema. At the same time, the gestural-painting string to his bow kept him very busy at many exhibitions about the new writing (at the Mercato del Sale and Avida Dollars galleries, Milan).

It was the radical movement, however, that used most of La Pietra’s energy – in running IN magazine, in producing the monograph magazine Inpiù, in editing the Global Tools journals, in the research of the Communication Group (with Gianni Pettena, Franco Vaccari and Guido Arra) within Global Tools, and in organising the sole exhibition on radical design “Gli abiti dell’imperatore” (The emperor’s clothes).

In the late 1970s, he found opportunities to communicate his experiences more fully and systematically, by teaching at the Istituto Statale d’Arte, Monza (1977), working on the great audiovisual-sector exhibition in the reborn Milan Triennale (1979), and editing the design and furnishing sector of Domus magazine (1979).

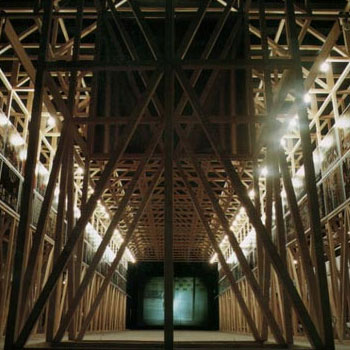

La Pietra is arguably the most representative author of that decade, with unconventional forms that made room in art for the joy and hope of new models of distributed creativity (extending beyond the art world), with new communication approaches (liberated from the centres of power and the manipulation of messages), with behavioural and design models that offered a new way to engage with the urban context: reappropriating the environment.

It would be precisely his meta-project experiences – the exhibitions, articles and seminars – that paved the way to the practice of Inhabiting the city, by developing a perspective that would prompt more and more operators to concern themselves with the urban environment in the early 1980s; the discipline of “urban design” was born.